Having grown up in rural Vermont, I have been

enthralled with William Morris’s News from

Nowhere since first reading it. Yet “rural” Vermont isn’t quite right. Like Morris’s Nowhere in the years immediately

after the revolution, my hometown was marked by both recently collapsed

industry and continued agriculture. Unlike, say, Middlemarch – the novel that first drew me to Victorian studies –

with its picture of provincial life as a mingling of manufacturing and farming, News from Nowhere spoke to my own past,

one where agrarian and craft labor had begun to supersede industrial

production. Above all, however, Nowhere’s folk mote – a utopian form of

community self-government -- resonated with my experience of progressive

politics within a small community where town halls still determine public

policy.

More

than an accessory of some pastoral idyll of New England,

the town halls of Vermont share ideological roots with

Morris’s folk motes. Both stem from a desire for what the fin de siècle

socialist John Morrison Davidson called “Politics without Politicians” – local

direct democracy, or, in the Socialist League’s terms, “management.”

To

model such local management, Morris recuperated the folk mote. Believed to be

the primary mode of British governance prior to the Norman

invasion, the mote represented to ictorian advocates of local self-governance a

model rich with associations of Anglo-Saxon self-determination and

anti-centralism. Until the 11th century, the “moot” served as an

assembly wherein a locality’s citizens would collectively deliberate upon

courses of action affecting the entire community. For localists like Joshua

Toulmin Smith and Morris’s contemporary, George Laurence Gomme, the moot was

both the common-law origin of local government and, accordingly, a model for

local self-governance in the present. Gomme’s Primitive Folk-Moots, for instance, recuperated the mote for

present-day government reforms, largely because, as constitutional historian

Williams Stubbs put it, “in the shire-moot, we have a monument of the original

independence of the population.”

In

his romances, Morris likewise resurrected the moot. The House of the Wolfings makes the “folk-mote” into the vehicle whereby

“the whole Folk . . . must determine what to do and what to forbear doing.”

Accordingly, two pivotal chapters -- “They Gather to the Folk-Mote” and “The

Folk-Mote of the Markmen” – detail the collective deliberation by the men of

the Mark over who will lead them into war. Similarly, The Well at the World’s End’s

culminating battle commences only after a shepherds’ folk-mote collectively

decides to band together and join Ralph in overthrowing tyrants who have taken

over Upmeads in Ralph’s absence.

|

| From the Kelmscott edition of The House of the Wolfings |

Morris

also grounds News from Nowhere’s

future, utopian “pure Communism” in the village-mote. As Hammond explains, “Matters Are Managed” in

Nowhere through motes localized in “units of management, a commune, or a ward,

or a parish.” They work thusly: “some neighbors” want “a new town-hall built; a

clearance of inconvenient houses; or say a stone bridge substituted for some

ugly old iron one.” The whole community debates if the parish will pursue such

a project at an “ordinary meeting of the neighbors, or Mote, as we call it, according

to the ancient tongue of the times before bureaucracy.” In utopian Nowhere,

that is, Britain’s archaic governing institution, once flourishing before the

rise of representative government, offer “pure Communism” what Guest calls

something “very like democracy,” the means whereby the community decides which

collective projects to pursue. It is through the mote, in other words, that

“the whole people is our parliament.”

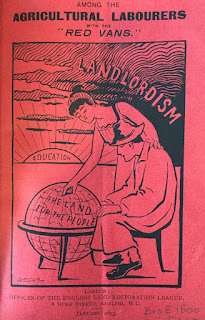

While

in 1891 such localized direct democracy remained either in Britain’s

ancient past or utopian future, the 1894 Local Government Act offered

agricultural laborers an institution capable of revitalizing the mote: the

Parish Meeting, a mode of rule whereby smaller communities could govern

themselves without elected representatives. The English Land Restoration League’s

Red Vans served as a crucial means for promoting agrarian radicalism. Launched

as a get-out-the-vote campaign for agricultural laborers, the Red Van’s tour

centered on the village meeting. According to the 1891 Red Van report, each

tour proceeded by “select[ing] a comparatively small area, and work[ing] a

county . . . thoroughly by means of village meetings.” The following year’s

report further specifies that “It has been the aim of the Executive to promote,

in each county, the establishment of a strong, solid, self-governing union of

labourers . . . No opportunity has been lost upon urging the labourers . . .

that their first duty is . . . to take into their own hands the management of

their own affairs.”

The

nearly 500 village meetings in 1892 alone offered occasions for agricultural

laborers’ deliberation on their collective needs and desires. The ELRL saw the

village meeting as modeling the localized public sphere it hoped would remain

in effect after the Van left town. Participants in these meetings would thereby

practice the type of self-organization and management needed “to produce,” in

the 1894 report’s words, “anything more than a mere ripple on the surface of

village life.” Meetings modelled the practices of “County Unions,”

which were to be “democratically constituted, managed by the labourers themselves.”

Understandably, after the 1894 LGA the Red Vans promoted the Parish Meeting as

the ideal institution for local self-governance – the Villagers’ Magna Charta’s detailed outline of the 1894 Act largely

reprints an ELRL leaflet and, in turn, the Vans distributed Davidson’s tract

beginning in 1894.

From

sanctuary cities to minimum wage reform, the local has once again assumed prominence in politics. And while Bernie Sanders’ call

for progressive local politics and the Democratic Socialists of America’s

recent successes in municipal elections are heartening, I worry that these

efforts might reiterate the metropolitan-rural divide characterizing national elections

in both America and Britain (as evidenced by the 2016 presidential and Brexit

votes, both of which followed a marked left/right, city/country divide).

Morris’s mote and the ELRL’s village meeting offer two models for grassroots

rural radicalism, models with existing frameworks in places like Vermont. Rural town

halls, after all, offer one venue for realizing a “politics without

politicians.”

--Michael Martel, UC Davis